Bounded Static Analysis

Everything Everywhere All at Once

Table of Contents

- What is Bounded Static Analysis?

- Abstractions

- Bounded Abstract Interpretation

- Getting Started

Proposal due Wednesday Evening after fall break.

But you can hand it in before.

Questions

Why should we use abstractions when analysing code?

What is the advantage of Galoi connections?

Which cases are the Sign abstraction not able to catch?

At which cases do your static analysis outperform your dynamic?

Feedback

Is this still fun?

What is Bounded Static Analysis? (§1)

In Theory (§1.1)

Breath-first!

May and Must Analyses (§1.2)

Abstractions (§2)

- The Sign Analysis

- Partially Ordered Sets (Posets)

- Lattices

- Galois Connection

- Abstract Operations

The Sign Analysis (§2.1)

is the abstractor

Partially Ordered Sets (Posets) (§2.2)

A partially ordered set

Examples

Integers in both directions

Sets

Signed

Why Partial Orders?

Lattices (§2.3)

Partial orders ,

meet ,

join ,

and has a smallest and biggest element.

Hasse diagrams. (§2.3.1)

A Hasse diagram over the poset . By I, KSmrq, CC BY-SA 3.0 (with edits)

Back to the Sign Abstraction (§2.3.2)

, , and

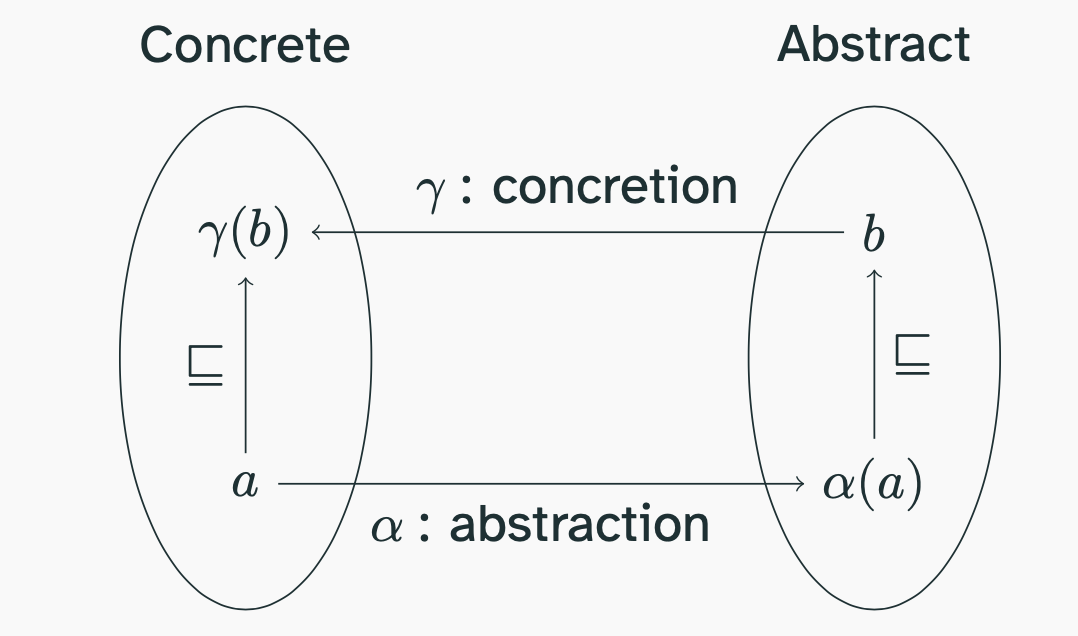

Galois Connection (§2.4)

(A Galois Connection is a connection between two ordered sets, with a concretion and an abstraction function.)

What are they good for?

A mathematical definition of one-sided information loss. If my abstraction finds a bug, is there a bug in the original domain?

A weak equality.

Laws For Free

Adjunctions and Testing

# Most of the time

parse(pretty(a)) == a

# Always

pretty(parse(pretty(a))) == pretty(a)

# Bonus for all strings s:

parse(pretty(parse(s))) == parse(s)Back to the Sign Analysis (§2.4.1)

Build the Sign Abstraction

@classmethod

def abstract(cls, items : set[int]):

signset = set()

if 0 in items:

signset.add("0")

...

return cls(signset)def __contains__(self, member : int):

if (member == 0 and "0" in self.signs):

return True

... Test your abstaction

from hypothesis import given

from hypothesis.strategies import integers, sets

@given(sets(integers()))

def test_valid_abstraction(xs):

s = SignSet.abstract(xs)

assert all(x in s for x in xs)Abstract Operations (§2.5)

Define the operation

Test your Abstract Operation

@given(sets(integers()), sets(integers()))

def test_sign_adds(xs, ys):

assert (

SignSet.abstract({x + y for x in xs for y in ys})

<= SignSet.abstract(xs) + SignSet.abstract(ys)

)Bounded Abstract Interpretation (§3)

To show , we need to prove:

But we can get away with

The State Abstraction (§3.1)

This is nice because

if , then

The Per-Instruction Abstraction (§3.2)

The Per-Variable Abstraction (§3.3)

Variable Abstractions (§3.4)

Abstractions All The Way Down. (§3.5)

Getting Started (§4)

Abstract Your Interpreter

Emit multiple states.

Start Small, Just One frame.

Emit multiple States

def step(state : AState) -> Iterable[AState | str]

...Do all states at once.

def many_step(state : dict[Pc, AState | str])

-> dict[Pc, AState | str]:

new_state = dict(state)

for k, v in state.items():

for s in step(v):

new_state[s.pc] |= s

return new_stateQuestions

Why should we use abstractions when analysing code?

What is the advantage of Galoi connections?

Which cases are the Sign abstraction not able to catch?

At which cases do your static analysis outperform your dynamic?